You are eating your lunch, biting into that delicious apple, when suddenly you have a severe electrical zapping shock across part of your face. You jerk your head back because of the extreme pain. And then just as fast as it came on, it’s gone again. You start freaking out, wondering what is happening. It starts to come and go more frequently. You start to dread being out in public because of the fear that you’ll get an attack again. This is a very typical story for trigeminal neuralgia, the most severe facial pain you can have in the face.

Unfortunately, we see many patients that have had similar stories and end up starting with the dentist first with subsequent teeth extracted and root canals without benefit. Eventually they end up referred to neurology or a headache specialist and treated for trigeminal neuralgia. So, if you are having these types of pains as described below, it is worth seeing a neurologist or headache specialist before considering any dental procedures. With that said, dental causes of facial pain (remember, the teeth are also innervated by distal branches of the trigeminal nerve) can certainly be in the differential as well, depending on the location, pattern, and character of the pain. There are also other types of facial pain, but essentially, they can all be boiled down into 4 main facial pain categories as you’ll learn below.

What is trigeminal neuralgia?

This type of facial pain has also been called tic douloureux because the attacks of pain are so severe that many jerk their head back and can cause contraction of the facial muscles. Some have also called it “suicide pain” because it can be so severe and debilitating. It is not uncommon to see patients who have had excessive weight loss because they are unable to eat due to the fear of triggering the facial pain. Common triggers include talking, chewing, brushing teeth, touching the face, cold air/wind on the face, shaving, using the phone to name a few of the common ones. However, the pain can also just occur regardless of any triggering activity.

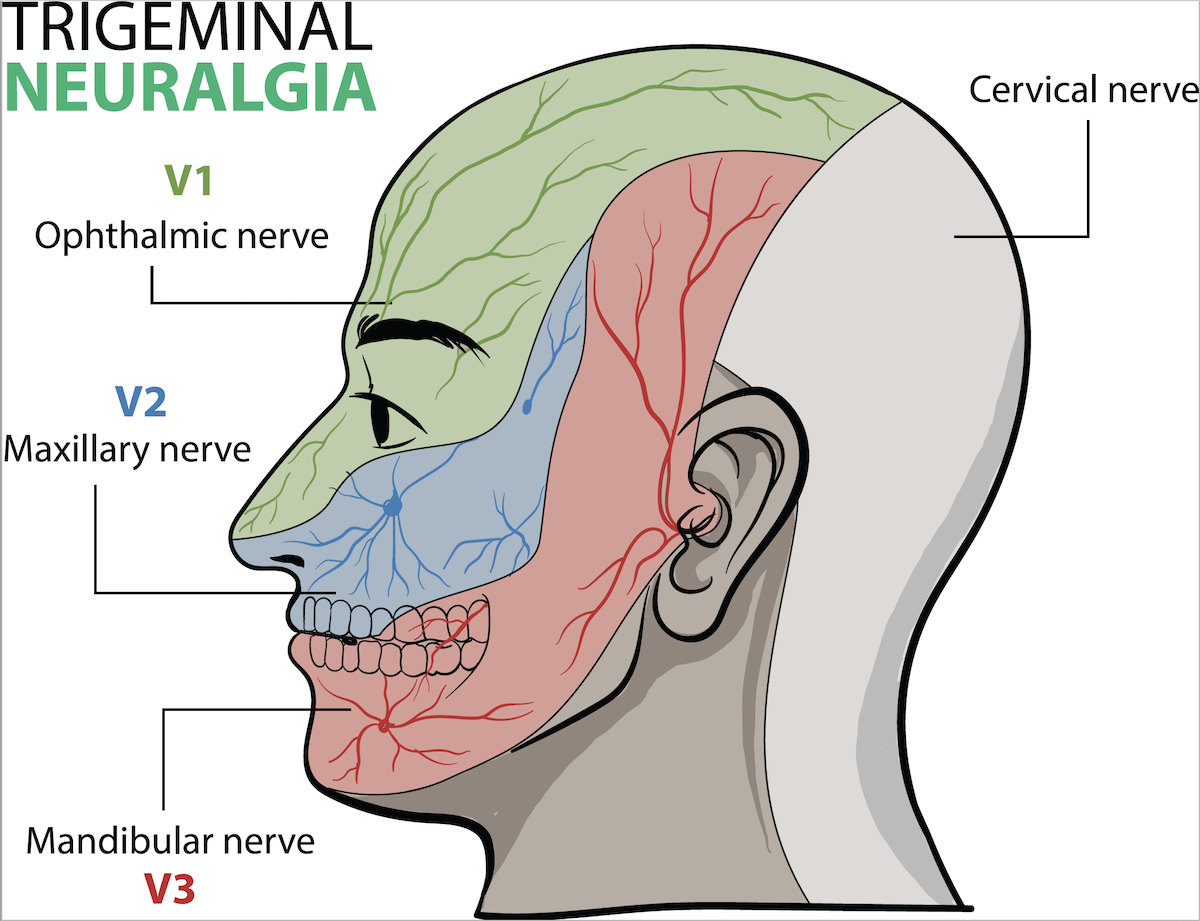

The pain occurs in one or more of the three branches (V1-3) of the trigeminal nerve; one branch (V1) travels into the forehead (also innervates the eyes and sinuses), one branch (V2) travels to the cheek area (also innervates sinuses and upper jaw and teeth), and one branch (V3) travels into the chin and jaw line (also innervates the lower jaw and teeth), as seen below. Trigeminal neuralgia occurs most commonly in the 2nd (cheek area) or 3rd (chin, lower face area) distribution of the trigeminal nerve.

How do you diagnose trigeminal neuralgia?

According to ICHD3 criteria, the pain occurs in sudden random attacks lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 minutes, and is of severe intensity. It is described as electric shock-like, stabbing, shooting, or sharp, and is triggered by stimuli to the affected side of the face such as touching, talking, brushing teeth, chewing, or cold air. Following a pain attack, there is usually a refractory period during which pain cannot be triggered by the usual stimuli that may trigger it. Mild autonomic symptoms such as redness or tearing of the eye on the side of the pain may sometimes occur. However, prominent autonomic features are typically absent, or very mild if they are present. Trigeminal neuralgia can be confused with one of the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (TAC) headache syndromes, which usually require much different types of treatments. So, it is important to make sure the diagnosis is accurate. We see many patients who are sent to us with a diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia, but many times it is not truly trigeminal neuralgia, but some other facial pain disorder.

Who does trigeminal neuralgia affect?

Trigeminal neuralgia affects women (60%) more than men (40%), with an average age of onset around 53-57. However, trigeminal neuralgia can be found in all age groups. If it is found in younger patients, other evaluations to exclude other causes such as multiple sclerosis (MS) should be performed. If it occurs on both sides of the face, especially in younger patients, further evaluations are also necessary to exclude causes such as MS, Lyme disease, and Sarcoidosis to name a few.

What are the different types of trigeminal neuralgia?

There have been many changes over the years of trigeminal neuralgia classifications. The most current classifications include 3 general categories of trigeminal neuralgia; classical trigeminal neuralgia, idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, or secondary trigeminal neuralgia. Evaluations for trigeminal neuralgia and differentiating the type revolves around the results of a contrast brain MRI and MRA (MR angiography) with a trigeminal nerve protocol, as further detailed below.

Classical trigeminal neuralgia

If the pain attacks fit with the description and features above, and the brain MRI shows that the trigeminal nerve is being compressed by a nearby blood vessel (neurovascular contact) causing morphological changes (such as swelling) of the trigeminal nerve on the side of pain, this is called classical trigeminal neuralgia.

Idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia

If there is neurovascular (blood vessel) contact of the trigeminal nerve without compression or no neurovascular contact, this is called idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia (idiopathic meaning we don’t know why the nerve is irritated and causing pain). Keep in mind that many times brain MRIs are done for other reasons and incidentally show a nearby artery in proximity or touching the trigeminal nerve. However, the patient may not have any facial pain issues at all. So, the point is that the clinical symptoms must be matched with the MRI findings because not all nerve contact by a nearby blood vessel may cause pain, or actually be the cause of trigeminal neuralgia, and can also just be that patient’s normal anatomy and unrelated to the pain.

Classical and idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia are both subdivided into 2 groups.

The 1st group consists of intermittent pain attacks (which must fit the main diagnostic criteria listed above) with pain freedom between attacks. This is called classical or idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, purely paroxysmal.

The 2nd group consists of intermittent pain attacks (which must fit the main diagnostic criteria listed above), but with a continuous or near-continuous pain in between those severe attacks in the same area of the trigeminal nerve. This is called classical or idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia with concomitant continuous pain. Studies have suggested that 14-50% of patients can have a continuous lower severity background pain in between the severe pain attacks.

Secondary trigeminal neuralgia

Secondary trigeminal neuralgia consists of pain attacks which fit the description above but are caused by something else (a “secondary” cause) such as a brain tumor, aneurysm, multiple sclerosis, or some other pathology.

What is atypical facial pain, or trigeminal neuropathy?

Atypical facial pain or trigeminal neuropathy are common terms for facial pain disorders which do not fit the type of pain pattern required by the ICHD3 trigeminal neuralgia criteria above, pain attacks going much longer than the allowed 2-minute maximum duration for attacks, etc. So basically, these are the facial pain disorders which do not fit diagnostic criteria for trigeminal neuralgia. These may be more of a continuous or fluctuating discomfort of a wide variability in character (burning, pressure, aching, throbbing, sharp, etc.). These pains can be from a variety of reasons such as dental, trauma, surgery, inflammation, demyelination (such as MS), infection, post-viral (such as Shingles/Herpes Zoster), compression, or most often from no clear reason at all which is identifiable (idiopathic). These types of facial pains are typically not as responsive to medications, procedures, or surgeries as true trigeminal neuralgia often is, so neurosurgery such as microvascular decompression is typically advised against. Atypical facial pain requires the same evaluations and testing as regular trigeminal neuralgia does to rule out secondary causes of the pain.

What type of MRI is needed for trigeminal neuralgia?

The contrast MRI and MRA should be done with a “trigeminal neuralgia protocol” which consists of a three-dimensional (3D) Constructive Interference in Steady State (CISS) gradient-echo T2-weighted, 3D time of flight and MRA, and 3D T1-weighted gadolinium MRI sequences. The MRI should be done on a 3.0 Tesla (T) or 1.5 T machine, although a 3.0 T resolution will more clearly delineate neurovascular compression of the trigeminal nerve. There is often confusion between CISS vs. FIESTA-C (Fast Imaging Employing Steady-state Acquisition) MRI sequences for trigeminal neuralgia evaluations, but these are equivocal. The CISS sequence correlates to Siemens MRI machines, whereas the FIESTA-C sequence correlates to GE MRI machines, but they are evaluating the same thing. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) for trigeminal neuralgia is a newer type of imaging test which can evaluate the nerve structure and myelination alterations because of neurovascular compression. This may eventually help to better identify which patients are more likely to benefit from microvascular decompression surgery. However, it is not currently used routinely in clinical practice and is more often being used in research.

How Long Does Trigeminal Neuralgia Last?

Individual attacks of trigeminal neuralgia last anywhere from a fraction of a second up to 2 minutes. After the patient has had multiple attacks triggered close together, there is often a temporary refractory period when the pain cannot be triggered. Trigeminal neuralgia flares can go into remission for months or years, but it is unpredictable. If there is neurovascular compression of the nerve by a nearby artery it is likely to flare up more frequently. For some patients it is chronic and unrelenting. In either case, a good treatment strategy must be sought to minimize its negative impact on the patient mentally, socially, financially, and medically (including being able to eat without pain being triggered).

What are the best treatments for trigeminal neuralgia?

This type of pain is of too short duration to catch it with an abortive, or “as-needed” treatment. Therefore, the goal of treatment is focused on preventive therapy; what to take on a daily basis to try to lessen the frequency and/or severity of the pain. Preventive medicines can take several weeks to start working, assuming the correct dose of the medication is reached. These are the medications most commonly used, although this is not an all-inclusive list.

Anti-convulsant (Anti-seizure) medications:

—Carbamazepine (Tegretol) (usually a 1st line option)

—Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) (usually a 1st line option)

—Gabapentin (Neurontin)

—Pregabalin (Lyrica)

—Topiramate (Topamax)

—Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

—Divalproex sodium (Depakote)

—Lacosamide (Vimpat)

—Zonisamide (Zonegran)

Anti-depressant/Anti-anxiety medications:

—Duloxetine (Cymbalta)

—Amitriptyline (Elavil)

—Nortriptyline (Pamelor)

—Venlafaxine XR (Effexor XR)

—Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq)

Muscle relaxants:

—Baclofen (Lioresal)

Analgesics:

—Opiates/Opioids (used for short term relief in the interim while longer term preventives take effect)

—Lidocaine gel or cream has limited usefulness

Biologics:

—Botox

Herbal:

—Copaiba topical essential oil. Copaiba is a resin that comes from the Brazilian Copaifera reticulata tree. It is very high in an important terpene called beta-caryophyllene (BCP) (which some have debated whether it is a phytocannabinoid). Beta-caryophyllene is also found in many strains of cannabis. It binds directly to CB2 (cannabinoid 2) receptors to affect the endocannabinoid system. CB2 receptors have a strong role in reducing inflammation. I mention this ONLY because I saw a patient have complete relief of his trigeminal neuralgia while he was using this topically. On days he would not use it, the pain would return. So it’s purely anecdotal, and unknown if clearly related or not. I have no data or studies to support it as a treatment. However, many people do use Copaiba oil for various pain and inflammatory conditions given its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

—Medical cannabis. Again, limited evidence and case reports have been published on this treatment and more studies are needed.

Blocks:

—SPG (sphenopalatine ganglion) blocks or SPG neurostimulation

—Trigeminal nerve blocks

Surgery:

—Microvascular decompression (MVD) (considered 1st line treatment in classical trigeminal neuralgia with neurovascular compression after failing medications, and most effective procedure for long term benefit)

Ablative Procedures:

—Gamma knife radiosurgery

—Glycerol injection

—Balloon compression

—Radiofrequency thermal lesioning

How do you decide what trigeminal neuralgia procedure or surgery to consider?

If patients fail conservative medication trials (or cannot tolerate them), and if there IS neurovascular compression of the trigeminal nerve on MRI, then microvascular decompression (MVD) is considered treatment of choice. Studies have shown that 62-89% of patients continue to be pain free in follow up after 3-11 years. Severe rare complications can include edema, bleeding, or stroke (0.6%), anesthesia dolorosa (0.02%), meningitis (0.4%), or death (0.3%). Less severe complications can include hearing loss (1.8%), facial numbness (3%), and cranial nerve palsy (4%).

If patients fail conservative medication trials (or cannot tolerate them), and if there is NO neurovascular contact of the trigeminal nerve on MRI, then ablative treatments are the preferred treatments. Studies show that during a follow up of 4-11 years, 30-66% were pain free with gamma knife, 55-80% were pain free after balloon compression, 26-82% were pain free after radio frequency thermocoagulation, and 19-58% were pain free after glycerol injection. Potential complications after these procedures overall are facial numbness (19%), corneal numbness (5%), trigeminal motor weakness (5%), anesthesia dolorosa (0.5%), and meningitis (0.7%).

If patients fail conservative medication trials (or cannot tolerate them), and if there IS neurovascular contact but NOT compression of the trigeminal nerve on MRI, then microvascular decompression (MVD) and ablative procedures are equal first line treatment choices.

IF YOU HAVE HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN AND ARE LOOKING FOR ANSWERS ON ANYTHING RELATED TO IT, A HEADACHE SPECIALIST IS HERE TO HELP, FOR FREE!

FIRST, LET’S DECIDE WHERE TO START:

IF YOU HAVE AN EXISTING HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN DIAGNOSIS AND ARE LOOKING FOR THE LATEST INFORMATION, HOT TOPICS, AND TREATMENT TIPS, VISIT OUR FREE BLOG OF HOT TOPICS AND HEADACHE TIPS HERE. THIS IS WHERE I WRITE AND CONDENSE A BROAD VARIETY OF COMMON AND COMPLEX MIGRAINE AND HEADACHE RELATED TOPICS INTO THE IMPORTANT FACTS AND HIGHLIGHTS YOU NEED TO KNOW, ALONG WITH PROVIDING FIRST HAND CLINICAL EXPERIENCE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF A HEADACHE SPECIALIST.

IF YOU DON’T HAVE AN EXISTING HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN DIAGNOSIS AND ARE LOOKING FOR POSSIBLE TYPES OF HEADACHES OR FACIAL PAINS BASED ON YOUR SYMPTOMS, USE THE FREE HEADACHE AND FACIAL PAIN SYMPTOM CHECKER TOOL DEVELOPED BY A HEADACHE SPECIALIST NEUROLOGIST HERE!

IF YOU HAVE AN EXISTING HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN DIAGNOSIS AND ARE LOOKING FOR FURTHER EDUCATION AND SELF-RESEARCH ON YOUR DIAGNOSIS, VISIT OUR FREE EDUCATION CENTER HERE.