What Is Syncope?

If you’ve ever had an episode of syncope (passing out, or fainting), you know how scary it can be for you, as well as everyone around you. It’s scary not only from the syncopal episode itself, but also trying to sort out the causes of the fainting episode. Could it be heart problems such as abnormal heart rhythms, a problem with the blood vessels in the brain, low blood sugar, a neurological condition such as stroke or seizure, or some other medical condition? Syncope is an extremely common condition, and also a common reason for visits to the emergency department leading to hospital admissions.

So what is syncope and what is the most common cause of syncope? Well, first let’s define syncope. Syncope is a temporary loss of consciousness typically due to a sudden change of lack of blood flow to the brain followed by collapse (syncope and collapse). The most common syncope causes are from either a drop in blood pressure while in the standing position (orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic intolerance, postural hypotension, postural syncope), or from a vasovagal syncope response (neurocardiogenic syncope, reflex syncope), or from the heart not pumping enough blood to the brain from an arrhythmia (heart temporarily beating too fast or too low), or a weak heart muscle (such as in congestive heart failure). “Near syncope” is the term for “almost” having a syncope episode. This is where you feel like you “almost pass out”, and perhaps briefly get dizzy, lightheaded, woozy, and unsteady.

Ok, you’re probably wondering why I’m talking about syncope on a migraine blog. Well I thought it would be a useful topic because syncope or pre-syncope (dizziness, orthostasis) often occurs with migraine attacks. This is most often due to a vasovagal response (see below) related to the severe pain of the migraine or dehydration from vomiting (which leads to lower blood volume, less perfusion pressure in the arteries, and ultimately a decreased amount of blood to the brain). However, many migraineurs can also have some degree of dysautonomia during an attack, but also at their baseline even when not having a migraine. Dysautonomia is a dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system controls blood pressure, arterial dilation or constriction, heart rate, heart rhythm, sweating, and gastric motility. Any imbalance within the autonomic nervous system can lead to dizziness and syncope. Various degrees of dysautonomia are commonly seen in patients with migraine such as gastroparesis, dizziness, POTS, and complaints of cold hands and feet which can be associated with discoloration (such as Raynaud’s).

What Causes Syncope?

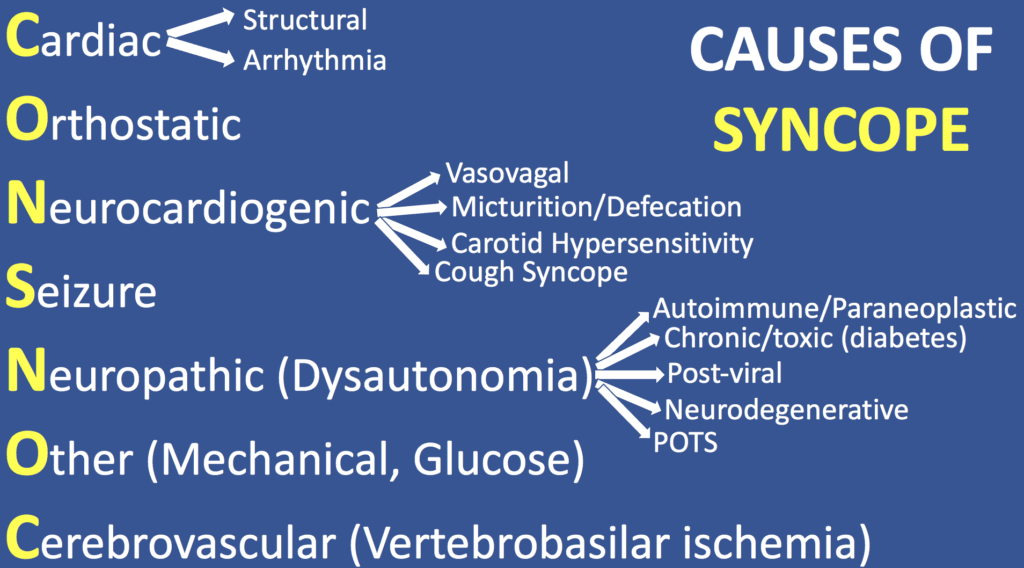

Syncope is rarely ever of a true neurologic cause. However, for some reason, this is still one of the most common reasons for neurology consults in the hospital setting. Therefore, I created a simple mnemonic tool that will help doctors and other healthcare providers consistently remember every possible cause of syncope to check off your differential diagnosis list of possibilities. I always teach this tool to the medical residents, fellows and medical students who are rotating on the inpatient neurology hospital service, because syncope is such a common reason for neurological consultation. This mnemonic can be helpful across all medical specialties since syncope is such a common event across all medical specialties. It can also be used by patients and their families suffering from syncope to help them gain a better understanding of the various types of syncope.

The mnemonic tool is CONSNOC. It’s a palindrome spelled the same forwards and backwards. It’s a nonsensical word, but remembering it will quickly bring to memory every possible differential diagnosis of syncope to run through in your mind. Let’s go through each letter:

Cardiac

Think the SA (sinoatrial) node, and then think Structural and Arrhythmia causes. Structural can be outflow obstruction or low ejection fraction in CHF (congestive heart failure). Arrhythmia can be from the heart beating too fast (tachycardia) or too slow (bradycardia). A heart attack, or myocardial infarction, is always a primary concern for syncope. All syncopal episodes should be evaluated by a cardiologist to exclude underlying cardiac diseases. All of these things ultimately lead to a lack of blood flow to the brain, followed by syncope.

Orthostatic

Orthostatic hypotension, or orthostatic syncope, occurs from low blood pressure which happens when someone stands up from a lying or sitting position. Orthostatic hypotension is the most common type of syncope. The body’s normal response from moving from a sitting or lying position to a standing position is that the arteries and veins in the legs and lower body constrict (tighten), preventing pooling of blood from gravity in the legs, and pushing the blood back up towards the brain and rest of body. The net result is that blood pressure is sustained in a continued normal level regardless of positional changes. The autonomic nervous system maintains this balance. When there is a delay or dysfunction in this autonomic nervous system response upon standing, there is a temporary drop in blood pressure which causes dizziness or syncopal symptoms (orthostatic intolerance, orthostatic hypotension). Dehydration or blood pressure medication doses that are too high are often common culprits of syncope.

Orthostatic intolerance refers to a variety of symptoms that occur when someone is in the standing upright position, related to a decrease in blood pressure. Orthostatic intolerance symptoms can include dizziness, lightheaded, fatigue, palpitations (skipping heart beat feeling), and vision may start to fade out, but the blood pressure doesn’t get low enough to cause them to pass out. This is also called pre-syncope. Orthostatic intolerance can be thought of as a “milder” or preceding form of orthostatic hypotension.

Orthostatic hypotension refers to a more significant drop in blood pressure which often coincides with fully passing out and having syncope. Technically, it is defined as a systolic blood pressure (the top number) drop of 20 mmHg or more, or a diastolic blood pressure drop (the lower number) of 10 mmHg or more, and/or an increase in heart rate by 30 or more beats all within 3 minutes of standing. Cold, clammy, pale skin, vision fading out or blurred, dizziness, nausea, palpitations, racing heart sensation, disorientation, and brief loss of consciousness are some commonly associated symptoms with orthostatic hypotension. The loss of consciousness associated with a syncopal episode typically lasts a few seconds to 30 seconds, up to about a minute or so. It rarely should go beyond a couple minutes.

I have listed a number of treatment suggestions to help with treatment or orthostatic intolerance and orthostatic hypotension a bit further down in this blog.

Neurocardiogenic

This is your classic vasovagal response where there is a sudden decrease in heart rate followed by an abrupt drop in blood pressure leading to syncope and collapse (passing out, or fainting). Some also call this situational syncope. It is common across all ages, especially in young adults. The physiologic mechanism for neurocardiogenic syncope can be triggered by several things. Vasovagal syncope classically occurs with a sudden scare (sight of blood, intense pain, fright, emotional distress, etc.). Variants of the vasovagal response also include micturition or defecation syncope (think about the old lady who passed out after standing up from using the toilet, triggered by a large parasympathetic discharge), carotid hypersensitivity/carotid sinus syncope (think about the old guy shaving and becomes bradycardic by inadvertent carotid massage from pressing on the neck during shaving), and cough syncope or syncope with coughing.

Seizure

This question is a common reason for inpatient neurological consult even though most syncopal episodes are almost never from a seizure, without being associated with a clear generalized body seizure and loss of consciousness. Look for additional symptoms such as tongue biting, incontinence, and witnesses to the event for description (preceded by staring off, posturing, tonic-clonic activity, etc.). Keep in mind, you can still have convulsions during syncope called convulsive syncope (syncope with convulsions), which are not true seizures but just a manifestation of sudden drop in blood pressure and lack of blood flow to the brain. Incontinence can also occur with syncope, so it does not confirm a seizure cause, but does raise suspicion with the right symptoms. The diagnosis of seizure is best made by the company it keeps (associated symptoms with the syncopal event).

Neuropathic

This correlates to dysautonomia, also known as autonomic neuropathy. This is neuropathy involving the small nerve fibers from the autonomic nervous system that control heart rate, heart rhythm, blood pressure, gastrointestinal motility, sweating, and other organ systems. The result is often a disconnect between blood pressure and heart rate where they are not working in synchronicity together, leading to symptoms such as syncope. For example, the body’s normal response to a drop in blood pressure causing orthostatic intolerance symptoms such as dizziness is that the heart rate increases in order to compensate for this drop. By beating faster, it gets more blood sent to the brain to offset the decrease from lower pressure. In an autonomic neuropathy (dysautonomia), if the blood pressure drops, there is not a compensatory heart rate increase to maintain brain blood flow, and syncope occurs. There are a wide variety of these disorders, but the top categories to keep in mind are from chronic/toxic autonomic neuropathy such as from diabetes, autoimmune dysautonomia (such as acetylcholine receptor (AchR) autoantibody, paraneoplastic), post-viral dysautonomia, or neurodegenerative dysautonomia (such as Shy-Drager Syndrome in Parkinson’s Disease). POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome) is another form of dysautonomia, although syncope is not as common of a symptoms for this.

Other

Think additional possibilities such as mechanical (the patient simply tripped or lost their footing), glucose (hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia).

Cerebrovascular

Think posterior circulation and vertebrobasilar ischemia from the blood vessels in the back of the brain and brainstem. This is the other most common reason for inpatient neurology consultation in terms of possible TIA (transient ischemic attack) or stroke, but again, syncope is rarely the result of this. If this is the cause, it is typically associated with other neurological symptoms, particularly of the posterior circulation. So, assess for associated brainstem symptoms such as double vision, hemiparesis or hemisensory loss (weakness or numbness on one side), slurred speech or trouble getting words out, vertigo, dysphagia, confusion, etc. Posterior circulation stroke isn’t the only location which could cause a fall or syncope though, so any new neurological symptoms warrant a stroke evaluation. Similar to seizures, syncope secondary to posterior circulation TIA, stroke, or any location stroke is best made by the company it keeps (associated neurological symptoms with the syncopal event).

Testing for Syncope Causes

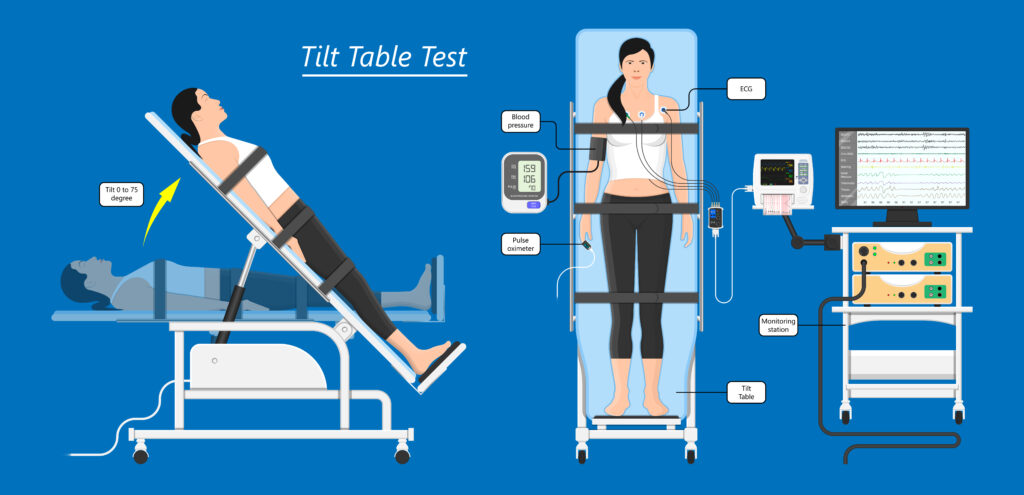

Orthostatic vital signs are the most basic test to first assess for if a person has orthostasis (drop in blood pressure and/or rise in heart rate while standing). This is done by checking blood pressure and pulse after the patient has been lying down for 5 minutes. The patient then stands up slowly. Blood pressure and pulse are rechecked after 1, 3, and 6 minutes. The test is positive or orthostatic hypotension if the systolic blood pressure decreases by 20 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure decreases by 10 mmHg, or pulse increases by 30 or more beats per minute.

A tilt-table test can help differentiate between many of causes of syncope. Any type of syncope should be evaluated by your healthcare provider including a physical examination. Cardiac causes are always the first thing that need to be excluded, so a cardiologist should always be involved in a syncope evaluation. If there is associated chest pain, this can be one of the warning signs of heart attack and emergent medical attention is needed. Testing should also include an EKG to check for ventricular tachycardia, long QT syndrome. Your doctor will likely order an echocardiogram to make sure the cardiac output of blood volume is normal and to rule out structural heart diseases such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (can be a cause of sudden death) or aortic stenosis.

Depending on the symptoms, history, and symptoms there may be additional testing done such as brain MRIs or CTs as well as MRA or CTA, or carotid ultrasound to look at the arteries in the brain and the neck (carotid arteries).

Treatment Of Orthostatic Intolerance and Orthostatic Hypotension

Orthostatic intolerance (orthostasis) is a common symptom and often a warning sign before a syncopal event, Here are some suggestions to help treat it. For severe cases, there are a variety of medications that can be used to treat it as well. However, here are some more conservative and easy things to do in treating and minimizing orthostatic intolerance and orthostatic hypotension to help prevent a full blown fainting spell.

- Make all postural changes from lying to sitting or sitting to standing, slowly.

- Drink to 2.0 -2.5 L of fluids per day. If you have a history of congestive heart failure (CHF), you should discuss fluid intake with your cardiologist to avoid a CHF exacerbation.

- Increase sodium (salt) in the diet to 3 – 5 g per day. If not helpful and blood pressure is stable, may try 5-7 g per day. If you have a history of high blood pressure, you should discuss these adjustments with your cardiologist or primary care physician.

- Avoid large meals which can cause low blood pressure during digestion. It is better to eat smaller meals more often than three large meals.

- Avoid alcohol. Alcohol and cause blood to pool in the legs which may worsen low blood pressure reactions when standing. This can aggravate OI.

- Perform lower extremity exercises to improve strength of the leg muscles. This will help prevent blood from a pooling in the legs when standing and walking.

- Raise the head of the bed by 6 to 10 inches. The entire bed must be at an angle. Raising only the head portion of the bed at waist level or using pillows will not be effective. Raising the head of the bed will reduce urine formation overnight and there will be more volume in the circulation in the morning.

- During bad days, drink 500 cc of water quickly. This will result in an increased blood pressure within 5 minutes of drinking the water. The effect will last up to one hour and may improve orthostatic intolerance.

- Use custom fitted elastic support stockings. These will reduce a tendency for blood to pool in the legs when standing and may improve orthostatic intolerance.

- Use physical counter maneuvers such as leg crossing, squatting, or raising and resting the leg on a chair. These maneuvers increase blood pressure and can improve orthostatic intolerance.

- Avoid temperature extremes, particularly excessive heat.

- For activity planning involving higher levels of physical activity, try to plan for:

-Before rather than after a meal

-Afternoon rather than morning

-Avoid excess heavy lifting

-Avoid during excessively hot weather

Syncope Treatment

How do you immediately treat syncope, and what is the immediate action for syncope? First, you want to make sure the person is in a safe area away from danger. Head injury can occur with a transient loss of consciousness and fall. So try not to move their head and neck around until they’ve regained consciousness to ensure they aren’t complaining of bad neck pain. If they do not regain consciousness right away, have a hard time getting up on their own, have any chest pain, shortness of breath, or neurological symptoms such as numbness, weakness, vision loss, slurred speech, trouble speaking, vertigo, or confusion, emergency medical services (EMS) should be called. If they can’t get up on their own, it is best to wait until the EMS personnel arrive to assist.

The optimal position of the patient as they are regaining consciousness should be flat on their back if safe to do so, and elevate the legs up by putting something under them. This helps return blood back to the brain. If the person is unconscious, it is often better to turn them on their side to maintain an open airway and prevent choking in case they vomit (which is not uncommon). Frequently check pulse and breathing. If they are unconscious and not breathing, CPR should be initiated to maintain blood perfusion to the brain, and emergency medical services called.

Otherwise, treatment of recurrent syncope revolves around conservative preventive measures. Does drinking water help syncope? The answer is yes for most cases of syncope, especially orthostatic hypotension or orthostatic intolerance. Water increases blood volume, and thus perfusion pressure to the brain to keep those neurons happy with fresh oxygen delivery.

Conclusions

Syncope can be frightening for patients, and for those around them. Trying to figure out which of the many possible causes may feel like looking for a needle in a haystack. However, going through the CONSNOC mnemonic will systematically walk you through all the possible causes to consider and narrow in on. Passing out, fainting, or syncope are very common events. They most often occur from orthostatic hypotension or a vasovagal response, but there are a variety of other considerations that should be taken into account, depending on the associated symptoms and history of the syncopal event. A physician should always evaluate all syncopal events to ensure no underlying cardiac disease (heart attack, arrhythmia, poor heart function). Additional specialists may be involved depending on the character of the syncopal event. The good news is that most syncopal episodes are from benign causes such as dehydration. However, syncope still warrants a conversation and evaluation with your doctor to be on the safe side.

IF YOU HAVE HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN AND ARE LOOKING FOR ANSWERS ON ANYTHING RELATED TO IT, A HEADACHE SPECIALIST IS HERE TO HELP, FOR FREE!

FIRST, LET’S DECIDE WHERE TO START:

IF YOU HAVE AN EXISTING HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN DIAGNOSIS AND ARE LOOKING FOR THE LATEST INFORMATION, HOT TOPICS, AND TREATMENT TIPS, VISIT OUR FREE BLOG OF HOT TOPICS AND HEADACHE TIPS HERE. THIS IS WHERE I WRITE AND CONDENSE A BROAD VARIETY OF COMMON AND COMPLEX MIGRAINE AND HEADACHE RELATED TOPICS INTO THE IMPORTANT FACTS AND HIGHLIGHTS YOU NEED TO KNOW, ALONG WITH PROVIDING FIRST HAND CLINICAL EXPERIENCE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF A HEADACHE SPECIALIST.

IF YOU DON’T HAVE AN EXISTING HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN DIAGNOSIS AND ARE LOOKING FOR POSSIBLE TYPES OF HEADACHES OR FACIAL PAINS BASED ON YOUR SYMPTOMS, USE THE FREE HEADACHE AND FACIAL PAIN SYMPTOM CHECKER TOOL DEVELOPED BY A HEADACHE SPECIALIST NEUROLOGIST HERE!

IF YOU HAVE AN EXISTING HEADACHE, MIGRAINE, OR FACIAL PAIN DIAGNOSIS AND ARE LOOKING FOR FURTHER EDUCATION AND SELF-RESEARCH ON YOUR DIAGNOSIS, VISIT OUR FREE EDUCATION CENTER HERE.